The intriguing Book of Zimbabwe – Part 3, from guerillas to diplomats

And so it begins

The pomp and ceremony is over now. The sun rises not over Rhodesia but over Zimbabwe. That long awaited day had come and we were free. It was time for the guerillas to morph into diplomats and technocrats. What must change and what must remain the same? Zimbabwe found herself in the middle of the infamous Cold War where the world was for all intents and purposes divided in two, pro-Soviet and pro-American, which was to say, pro-communist or pro-capitalist. Communist economies were failing all around the world whilst the capitalist ones were, by many standards, flourishing. The difficulty was that it was capitalist systems that had oppressed us in our recent history and it was communist systems that helped the most to get us out of this bondage. But again, history told us that communism had not enjoyed much economic success, whilst on the other hand, history also told us that capitalism created wealthy minorities and less affluent majorities, so then which end would Zimbabwe lean? The people had been promised prosperity for all and clearly, neither system could assure that. What choices then did the country have? Who were to be our friends and who were not?

Move two . . .

Now, a country as small and as young as Zimbabwe needed all the friends she could get, and as few adversaries as possible. She required technological and financial support from all who were willing to give. The new leadership knew this and made a wise choice. They elected to align themselves neither east nor west. Instead, Zimbabwe decided to join a group of nations calling itself The Non-Aligned Movement, NAM, a move that was to pay off in the later years of the developing Zimbabwe. NAM is today a group of circa 120 mostly developing nations that stood then and still stand today to benefit from partnerships with both sides. Also of great significance was the fact that should the Cold War have escalated into a full-fledged nuclear or other combat war, it was a lot safer and economical to be on the outside looking in, than to be involved in a bruising battle between superpowers. These countries simply did not have the financial nor human resources to commit to war, and a lot of them were, like Zimbabwe, African countries that were themselves recovering from the punishing consequences of their own liberation struggles or were grappling with finding political stability years after their own independence. It would not have made any sense to place themselves in yet another warpath. Instead, they needed to focus on delivering on the promises made during their various quests for self determination. They also had a common objective in protecting their own interests in common solidarity against international power blocs. The late former President of Cuba, Fidel Castro, summarised the purpose of the movement in his Havana Declaration of 1979 in which he outlined the movement’s aims as to, ensure “the national independence, sovereignty, territorial integrity and security of non-aligned countries” in their “struggle against imperialism, colonialism, neo-colonialism, racism, and all forms of foreign aggression, occupation, domination, interference or hegemony as well as against great power and bloc politics.” Deciding to join the Non-Aligned Movement was Zimbabwe’s second real diplomatic score. You may be wondering why I refer to this as the second diplomatic score and which then was the first?

Move one . . .

The first real diplomatic hurdle was crossed much earlier, even as the war for independence was raging. While the government that now stood at the helm of Zimbabwe was composed slightly different from that which the populace had believed would emerge from the war leadership, the ideologies that gave birth to the just ended war lived beyond the lives of some of the men and women that conceived them. One may appreciate that after a hundred years of subjugation, the most natural thing is for the newly liberated to deal retribution to their former masters. This is in fact the manner in which events had played out in other countries elsewhere around the world. Upon attainment of independence, some of these countries opted to expel the white population that had previously held them, and in some cases, forcibly took over businesses from non-indigenous people. With the departure of these “foreigners” as they were perceived and labeled, left the expertise of numerous decades and the financial resources that would have otherwise helped build successful economies in these countries. I suppose that this is the true value of history, to ensure that mistakes previously made are not allowed to recur and that the good deeds of the past are remembered and repeated wherever possible. In the case of Zimbabwe, even as the conflict raged, the then war leaders such as General Josiah Tongogara maintained that it was their dream to establish a motherland of equals where they could see, “the young people enjoying (life) together. Black (and) white (people) enjoying together, in a new Zimbabwe. That’s all.” This was the planting of the seed of reconciliation which was to be the first real diplomatic score of the coming black government of Zimbabwe. Thus, the eventual declaration of reconciliation at independence propelled the then Prime Minister Robert Mugabe onto the international arena as one of Africa’s truest statesmen and assured economic support in the nation’s endeavors to give of the promises of the war. Initially, a large proportion of the white population were apprehensive about Prime Minister Mugabe and his government which was seen as Marxist and represented an ideological win for communism. Many white people elected to leave the country or at least prepared an exit plan for when the imagined risk crystalised. It took some doing but as the years rolled by, the races slowly but painfully began putting the past into the past and looked ahead into the promising future.

Forging an army and a nation

As these events were playing out, another seemingly less important exercise was being carried out in the obscurity of the background. It didn’t really catch as much attention from the media or the public as it should have, and it was generally regarded as a necessary closing chapter for any war. Some news outlets did pick up on it, but reporting was initially infrequent, skimpy and in many cases did not recognise the huge importance of the exercise for the stability of the immediate future. As a result, and in the euphoria of the time, I don’t think that most people realised that they were happily walking around inside a potential tinderbox, just waiting for a trigger. So, what was going on? It was the disarmament and demobilisation of former combatants. The war was over and it was time for these gallant men and women to lead new lives in the land they fought to liberate. For several months, these former combatants or war veterans as they came to be known, were given an opportunity to surrender their weapons at various centers throughout the country. This was part of the Government’s drive towards disarmament as well as to facilitate the creation of a new standing national defense force. The majority of the ex-combatants willingly heeded the call to disarm, and many of those that gave up their arms were drafted into the new unified army or into civilian positions in the public sector. Some of them took up studies and private sector jobs alongside the non-combatant majority, and others retired among the civilian population, fatigued by many years of bitter struggle. It was the end of the past and the beginning of the future. It was a new start for everyone, the beginning of the rest of their lives. No one could have known at the time that this apparently small mass of retirees was to again play a major role in shaping the political and economic future of Zimbabwe in the coming decades. In order for this to happen, there were certain other factors that first needed to come into play. The groundwork for these had already been laid in part at Lancaster, and also in the skepticism of some of the ex-combatants from one of the two largest black military groups that fought in the liberation war. The first and most major of these factors was question number nine, the question of land, and although the Lancaster House conference made an attempt to address this, it offered no comprehensive solution to the problem. The consequence of that failure was to be felt years later by all in Zimbabwe and the immediate region at large. The second important factor was a tribal fracture that historically, but not so quietly, existed between the north eastern and south western indigenous people of the country. Although the north-south split is not absolute, it is generally representative of the distribution of the population, at least as far as the tribal subsets are concerned.

Zimbabwe’s First Constitution

Broadly speaking, the unwritten agreement at Lancaster referenced above, was that the British and US governments would help fund the acquisition of land from British citizens or descendants who had unlawfully expropriated land from the indigenous people. No costs were to be incurred by the incoming government which clearly was going to be a black majority. To help protect the interests of the minority whites, and also to minimize economic disruptions, the authors of Zimbabwe’s first constitution agreed to reserve twenty seats in the new Parliament for this small minority in elections provided for in the agreement. The rest were to be contested in general elections in which for the first time, the native population was to vote. The idea in itself was noble, but there were elements such as former Prime Minister of Rhodesia, Ian Douglas Smith, who would have preferred to see it all crumble. However, the planned elections went ahead, following which, Ian Smith continued as Rhodesian Front party leader and Leader of the Opposition in Parliament. Fortunately for Zimbabweans, the ambitions of this bitter old man for the black-led Government to fail, remained largely unachieved and the formations of successive majority black governments pressed on with several years of success lying ahead. Although Ian Smith, remembered in history for siring the infamous Unilateral Declaration of Independence, or UDI, continued to hold onto his negative views on black Africans, – “the more we killed, the happier we were,” – he once said about black freedom fighters, both he and his party were to soon find themselves out of Parliament and insignificant in Zimbabwean politics. Even though the Rhodesian Front rebranded itself to the Republican Front sometime in 1981, in hopes to distance itself from its past, this did not save it from its inevitable demise. A further renaming to the Conservative Alliance of Zimbabwe and an attempt to recruit black membership also met a similar fate. Once asked to give his opinion on the possibility of majority rule in the then Rhodesia, Smith famously declared, “not in a thousand years”, and it was somewhat fitting that he was to live out most of his remaining years in a liberated Zimbabwe, under black majority rule. Despite the racist positions he held on to, throughout, and likely beyond his political career, Smith was, for most of his life, allowed to continue to live freely in Zimbabwe carrying out farming activities and maintaining a fairly stable and exemplary family life. Setting his racist positions aside, it is fair to say that from a developmental perspective, successive minority governments, including the Smith regime, achieved spectacular economic and infrastructural development even in the face of sanctions imposed on the country. Much of the infrastructure in existence today, is a legacy of colonial administrations. The sanctions had been slapped on Rhodesia in response to the Smith government’s independence declaration from Britain over differences with regards to the issue of black majority rule. The British had insisted that majority rule was the only way forward to end strife in the country, but the Smith regime would have none of it. In the end, the combined weight of sanctions and military pressure from local armed resistance, had forced Smith and his government to capitulate to the wishes of the people, leading to the first inclusive elections in the history of the country.

Understanding ZANU and ZAPU’s delicate history

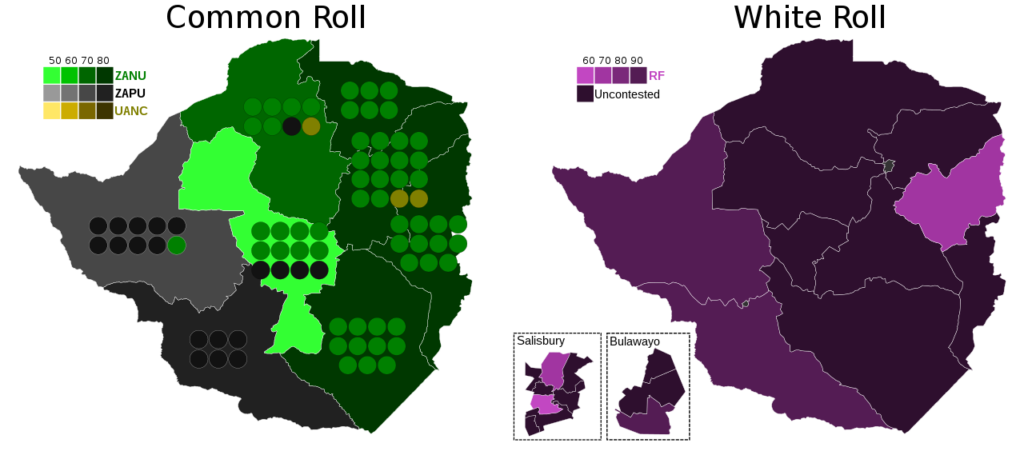

Allow me to now return to the issue of tribal fracturing among the blacks in more detail. This is important to provide more context to the story as it develops. In February 1980, the first multiparty elections were held, and also for the first time, black people were allowed to vote. In terms of the Lancaster House Agreement arrived at by the parties to peace negotiations concluded in December of the previous year, one hundred Parliamentary Seats were to be put to the vote. We have already noted that twenty of these seats were to be reserved for white minority candidates, ostensibly to help with fostering trust and also to smoothen the foreseen transition, among several other considerations. This left 80 seats to be contested for by the indigenous political parties. Predictably, the vote handed a resounding victory to ZANU, taking 57 of the seats on the back of by far the largest indigenous group in the country, the Shona. Although several different dialects and customs existed and continue to exist today among the Shona, what they have in common is more than what they have in difference. This made it easy for them to coalesce behind the Shona speaking Robert Mugabe and his ZANU ensuring him an indisputable landslide victory. That said, ZANU was not the only ethnicity-based party that contested in the election. The Zimbabwe African People’s Union, ZAPU, which garnered wide support in Matebeleland to the south and south-west, also contested in the election, headed by party leader Joshua Nkomo and winning 20 seats. Although much of the leadership in ZAPU were Shona, the fact that its leader was Ndebele caused the entire party to be viewed as Ndebele hence its appeal among the people from Matebeleland and less so among Mashonaland people. The remaining three seats were won by a minor party, the United African National Council or UANC. The UANC was led by Bishop Abel Muzorewa, a little respected former Prime Minister of a short-lived compromise government of Zimbabwe-Rhodesia that had been born out of a hollow and poorly conceived Internal Settlement. The settlement had been rejected by both ZAPU and ZANU and also failed to gain international acceptability. This, along with mounting pressure from the ongoing war for independence, had compelled the white minority government of Ian Smith, to come to the negotiating table at Lancaster at the behest of the British government.

Credit: FelipeRev – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=124431282

Of further importance to the gathering storm, was the fact that ZANU is a party that broke out of ZAPU over misgivings about the leadership’s methods and tactics towards the goal of independence. The split in the party was a source of disquiet and mistrust between the two formations which lasted past the national independence that both parties had fought for. It further entrenched divisions that reflected as a tribalistic tendency in Zimbabwe’s voting patterns for many years to come. Coming out of a racially charged war as we were, it is understandable that people would want to see their own in positions of authority in order to protect their interests. The distrust that remained among the indigenous population from different ethnicities, formed an invisible fracture that was masked over for the sake of nation building. In an interview aired on BBC’s Newsnight not long after the election result had given Robert Mugabe the victory, Joshua Nkomo flatly refused the possibility of conflict between the Shona and Ndebele people. In fact, he denied that the Shona and Ndebele were tribes, arguing that they were in themselves, collections of tribes and in many ways he was correct. It is respectable that he sought to put this point of view out amongst the people because it was a unifying message that tried to minimise the differences and amplify the oneness of Zimbabweans. Eventually however, his message could not stop a fallout between these two umbrella groups leading to a dark period in Zimbabwe’s history known as Gukurahundi. It is a difficult, divisive and emotive topic to discuss with successive Parliaments having failed to address it up to this point. Previous and current attempts to do so, have so far fallen short of actually providing a solid platform to bring some measure of closure for the victims and their families. Perhaps the one spark of hope is that the current government is making some effort to acknowledge that something went terribly wrong and requires addressing. The how and when are matters still to be fully dealt with after wide and transparent consultations with the aggrieved as well as other relevant stakeholders. After all, Zimbabweans are Zimbabweans first, before they are a race, a tribe or a political party.

Still more to come . . .

Subscribe, share the link and join us in the next instalment, where we discuss Gukurahundi and other developments that shaped the Zimbabwe we know today.

2 Comments