The intriguing Book of Zimbabwe – Part 5, Roses & thorns in the economy

“It’s complicated” – The relationship with apartheid South Africa

As the political machinery rumbled on, consolidating power for Mugabe and his party, the economy also needed attention. Keeping the economy thriving was another difficult task for Zimbabwe’s early government, in that it presented a unique conflict of interest for the black government. Allow me to explain.

You will recall that following the UDI, the United Kingdom and its allies imposed a set of punishing sanctions on Rhodesia in an effort to force Ian Smith and his government to modify their behavior. However, with the aid of South Africa’s apartheid system, Rhodesia was well able to bust most sanctions and even managed to create a strong and stable economy. In doing so, trade linkages between land-locked Rhodesia and South Africa became almost inextricably linked. Rhodesia became hugely depended on South Africa for export trade through the Beitbridge border post, a situation that subsists to this day. As much as 75% of Rhodesia’s, and later Zimbabwe’s exports were traded by rail through this port.

After Zimbabwe’s independence, the racist white minority government in Pretoria found themselves increasingly surrounded by nations led by black liberation movements. In order to maintain its position of power in the region, the apartheid government began a series of coordinated sabotage attacks on alternative trade routes in Southern Africa. They systematically bombed railway lines as well as bridges in many countries leaving only those that were either too dangerous, too long or too expensive for traders in the region to use. These hostile acts eventually left all the regional countries with no option but to channel most of their trade through South Africa. This was especially true for Zimbabwe whose other trade route, the Beira Corridor, was under frequent attack from Mozambiquan rebels fighting in a civil war in that country. The rebels in Mozambique were aided, at least in part, by the settler government in South Africa. The Beira Corridor, which consisted of a railway line, a road and an oil pipeline, was an important alternative trade route for Zimbabwe and supplied nearly all the petroleum requirements for the country. Even after Zimbabwe deployed a 12,000-person strong military force to guard the corridor, insurgent attacks, although fewer in number, continued almost throughout their deployment and this was extremely disruptive to the country’s economic activity.

Faced with this situation, Zimbabwe had no choice but to continue to trade with, and through South Africa, notwithstanding the clear conflict between its black nationalistic interests and South Africa’s globally condemned apartheid system. Although Mugabe’s administration had said it would impose sanctions on South Africa as part of efforts to support the black liberation movement in that country, the economic and geographic reality of South Africa made such sanctions impossible to achieve without harming Zimbabwe’s own economy. In fact, business leaders in the country were almost unanimously opposed to the idea of imposing any sort of sanctions on South Africa, because local industry heavily depended on it for machine parts, essential lubricants and agricultural chemicals. It also did not help that other countries in Southern Africa with whom a coordinated approach would have made an impact, were unwilling to commit to the sanctions, fearing the ramifications on their own economies. Of further important consideration, was the risk of Pretoria sponsoring further acts of sabotage on Zimbabwe, should the country have led the sanctions action on South Africa. Many such attacks had already happened, making this a threat, one that could have quickly crystalised and difficult to contain.

Another concern was that the South African administration had the power to delay processing goods transiting through their country, and where such goods were perishable or essential to manufacturing in Zimbabwe, the cost of delays would have been catastrophic for the country’s economy. In fact, the Pretoria administration once demonstrated this leverage by increasing the processing time for goods in transit from 13 days to as long as 40 days. After some negotiations, they later agreed to reduce this to 18 days but the message had clearly been sent to the administration in Harare, that they needed to tread with care when dealing with their neighbor to the south. These were some of the reasons that Prime Minister Mugabe’s public messaging consistently said his country would not involve itself militarily in assisting the liberation movement in South Africa. Yes, it went against the ethos of injure one, injure all, but was necessary to keep the economy functioning. In any event, a stable Zimbabwe was more useful in supporting the black resistance effort in South Africa in other ways that were not military confrontation. When looked at today, many people often focus only on Zimbabwe’s refusal to involve its military in South Africa, forgetting the complex relationship that existed between the two countries. Years after the end of minority rule in South Africa, that same complexity has, in many ways, continued to inform the ruling ANC’s diplomatic policy towards Zimbabwe. The African National Congress or ANC, is also a liberation movement rooted in black nationalism. It has, since its election, remained very pragmatic in its foreign policy position towards Zimbabwe. Given the developments in Zimbabwe in the late 1990s and beyond, the ANC is probably the one entity with the strongest hand with which to persuade Harare to implement necessary reforms – but this is the subject of a later discussion.

. . . the roses

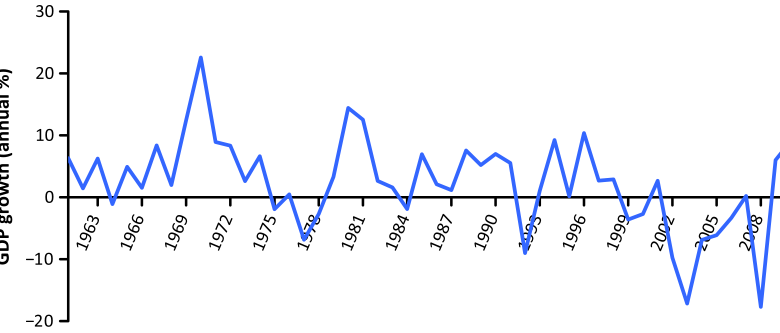

As it came into power in 1980, ZANU PF inherited one of the most diversified economies on the African continent. The Rhodesian economy had grown as private enterprise but after the UDI and subsequent sanctions, had to contend with some measure of government control. Import and exchange controls were implemented and strategic marketing boards became critical to establish and maintain prices and also to manage national food reserves. Most of this structure survived the government changeover, and although the first budget tried to sprinkle-in aspects of the new government’s socialist agenda, it was cautious in making sure that any policy shifts were gradual and not overly disruptive to the economy.

Agriculture

proud home of world famous brands

With vast tracts of fertile land, a favorable climate and a young labour force, agriculture had by 1980, become a mainstay of the economy and also the largest employer by numbers. It traditionally contributed as much as 15% of the gross domestic product (GDP). So large was the output, particularly of grains, that the country was able to feed itself, maintain a grain reserve as well as export excess food into the region, earning it the title, the bread basket of Africa. This was on the back of large, white controlled commercial farms supported by subsistence farming among the poorer black people who had long been dispossessed of their farmlands with the coming of white settlers in 1897. Crop production was also highly diversified, from maize – a local staple, to coffee, wheat, cotton, sugar, peanuts, berries, oranges, bananas, macadamia, apples, potatoes, sorghum, barley and the main cash crop, tobacco. Flowers grown in the country were also regularly exported to Europe and other far-off destinations. Dairy production was likewise performing very well whilst livestock farming was practiced throughout the country, especially cattle in the Matebeleland region where the Cold Storage Commission set up its headquarters. Organic beef from the region was also highly prized and easily found its way into the European export market. It is said Zimbabwean beef and tea were regular features on the Late British Queen’s table. High-end goat breeding, piggeries, fisheries and chicken farming were firmly established in various parts of the country. Many other agricultural subsets existed at the time but are not listed here, however, this should give the reader a good sense of just how much activity was going on in the sector and also why the fast-track land reform program of the later years had such a huge impact on the economy.

Manufacturing

Manufacturing was also a vibrant sector of the economy, taking a share of at least 10% of the GDP. With so much primary production on the farms, it made sense that a food processing base would grow on the back of the national agricultural output. The industry leapfrogged immensely after the UDI as efforts to counter sanctions meant that the country had to increase its self-sufficiency. As a result, more than 90% of manufactured goods used domestically were being produced by local industry. At first, the quality was not the best, but years of experience and refinement improved the product quality and created some much loved domestic brands that remain in existence in the country today, several of which eventually achieved export quality status. A similar shift to domestic production is increasingly taking hold under the current regime of US and European Union (EU) sanctions and other restrictive measures.

Mining

Photo Credit: Greenshoots Communications/

Alamy banque d’images

Mining was another important contributor to the economy. Zimbabwe is endowed with vast mineral wealth ranging from diamonds to gold, platinum, coal, lithium, nickel, cobalt, chrome and more recently, oil and gas exploration projects are underway. Gold was mined and locally refined at the Central Bank owned Fidelity Printers and Refinery. A large quantum of it was used to build a gold reserve securely housed at the Reserve Bank which helped maintain a stable and strong currency exchange rate. Most other minerals were extracted and exported raw for lack of refining machinery, but the export revenues were still helpful in boosting national earnings and foreign currency reserves. Diamonds were not yet officially being mined, but it is altogether possible that some elements within the country were aware of the alluvial diamonds in the Marange Fields of eastern Zimbabwe, and these were being surreptitiously shipped out of the country for individual benefit. Several other minerals like copper, silver, emeralds and asbestos also occur in the country and were being formally extracted, processed and used locally or were exported. Most of Zimbabwe’s coal was being mined in Hwange and used domestically for electricity generation, mainly at its Hwange Thermal Power installation which was expanded in the first decade of independence and then again in the early part of the 2020s. Lately, a small but growing quantity of coal is beginning to reach export markets like China. Reports also say that the EU is courting the Harare administration for access to its coal following an energy crisis in Europe caused by Russia’s military adventure in Ukraine. Uranium has been known to exist somewhere in the Zambezi valley but had not been considered for mining until recently because of the sensitive nature of the mineral as it relates to nuclear technology. The current President, Emmerson Mnangagwa, revealed that in his time, President Mugabe had explicitly refused to allow any mining of the uranium citing the same sensitivities and global security issues. However, President Mnangagwa seems to indicate his willingness to shift from this policy position on uranium. It remains to be seen what will come of it.

There was more going for the economy

There was, of course, a lot more going for the economy. Construction, tourism, trade and finance were all well integrated with the rest of the economy. Foreign exchange was streaming in from tourism and from exports of raw and finished goods. However, for a young and developing country like Zimbabwe with many social imbalances and lagged development among the black population, self-generated income alone was not going to be enough. Ian Smith’s government and the white minority governments before that, had pursued a policy of separate development. This policy of racial segregation saw white areas receive massive infrastructural investments whilst black areas received little to no investment at all. Areas set aside for Indians and people of mixed-race also known locally as coloured people, who, in Zimbabwe, are considered a separate race, received middle-of-the-road developmental investment. As a result, a lot of catch-up work needed to be done in the new Zimbabwe to bring about racial equity, and this is where developmental aid, international loans and grants came into play. After attainment of its independence, the country began receiving large amounts of money as aid, external loans and grants to assist in its social development programs such as increasing general access to public education, health, transport infrastructure, housing, power, water and sanitation. This aspect of developmental assistance, in whatever form, is important to note because seemingly unrelated events, playing out at home and somewhere in Central Africa, were coming together to precipitate a collapse so calamitous that it is one to be recorded for the history books. But before Central Africa, we must first talk about another thorn at home that was about to puncture a hole and deflate the economy.