The intriguing Book of Zimbabwe – Part 11, Hyperinflation

Hyperinflation and the multiple deaths of the Zimbabwe Dollar

Earlier on, we saw how a number of factors converged to militate against the local currency and drive hyperinflation. Some were beyond government’s control but others resulted from actions where better choices could have been made. The unforeseen effects of droughts are forgivable, unlike the fallout from ESAP, war veterans’ bonuses as well as the involvement in the DRC war which were unnecessary. The uncooperative positions taken by white farmers with regards to the government’s land redistribution program were unfortunate, and in the end, had detrimental consequences for both sides. For whatever reason, Britain’s decision to renege on its Lancaster House commitments escalated a situation that could have otherwise been contained, and went on to precipitate two decades of instability for one of Africa’s youngest nations. We examine here how these components brought about the first and later deaths of the Zimbabwean Dollar.

A brief recap of the story so far

When Zimbabwe became independent in 1980, it converted the national currency from the Rhodesian Dollar to the Zimbabwe Dollar (ZWD) at a factor of 1:1. At that time the ZWD was stronger than the United States Dollar (USD) and this remained true for a few years. The country enjoyed economic success for almost a decade before fractures began to appear with low job creation, price instability and slowing growth. Under rising political pressure, the government had taken a decision to pay bonuses to war veterans at great expense to the national budget. They also embroiled themselves in a civil war in the DRC prompting Western lenders and donors to review their financial support to Zimbabwe. The result of these actions were huge budget deficits which the government tried to cover through domestic borrowings and money creation. The obvious outcome of these poor remedial strategies was high inflation.

When ESAP was adopted in the early part of the 1990s, the prices of basic commodities rose even faster than before as the government began removing subsidies that had previously kept retail prices low. Widespread droughts that hit two agricultural seasons before 1995 led to a drop in agricultural output and subsequent food shortages and more price increases. Britain’s withdrawal from supporting land reform abruptly closed a valuable avenue for foreign budget support. A currency crash in November of 1997 principally fomented by the domino effect of the aforementioned bonuses turned a bad situation into a desperate one. The compulsory land redistribution exercise that was undertaken in 2000 after an unsuccessful earlier program from 1992 all but sealed the fate of the economy and its currency. The rise of opposition politics and the adversarial involvement of the West invited US and EU sanctions on the country. At this point, the catastrophic collapse of the economy could no longer be avoided.

Runaway inflation turns hyper

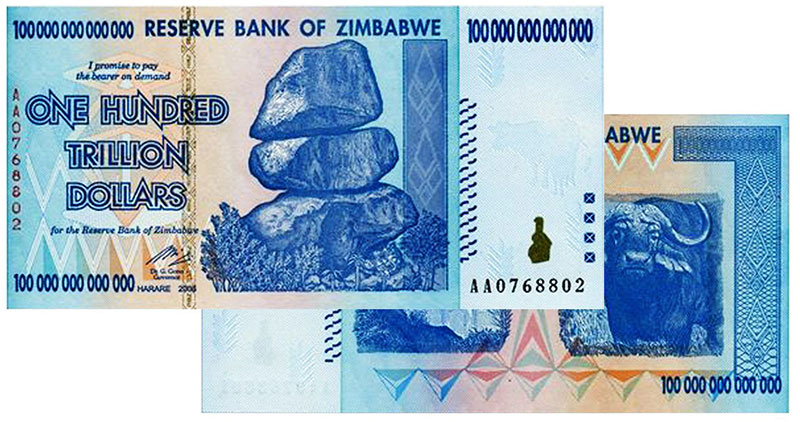

All the while, the rate of inflation continued to soar, officially turning hyper for the first time in February 2007. The Central Bank devised many interventions in-between to try and tame inflation but without success. The value of the currency fell dramatically resulting in some of the highest value bank notes ever printed whilst coins fell out of use because they simply no longer had value. At independence, the country had four bank notes in circulation with the highest value note being a twenty-dollar bill. At its worst, the Central Bank had issued a 100 trillion-dollar bill ($100,000,000,000,000) but not before having revalued the currency three times, slashing off a combined total of 25 zeros.

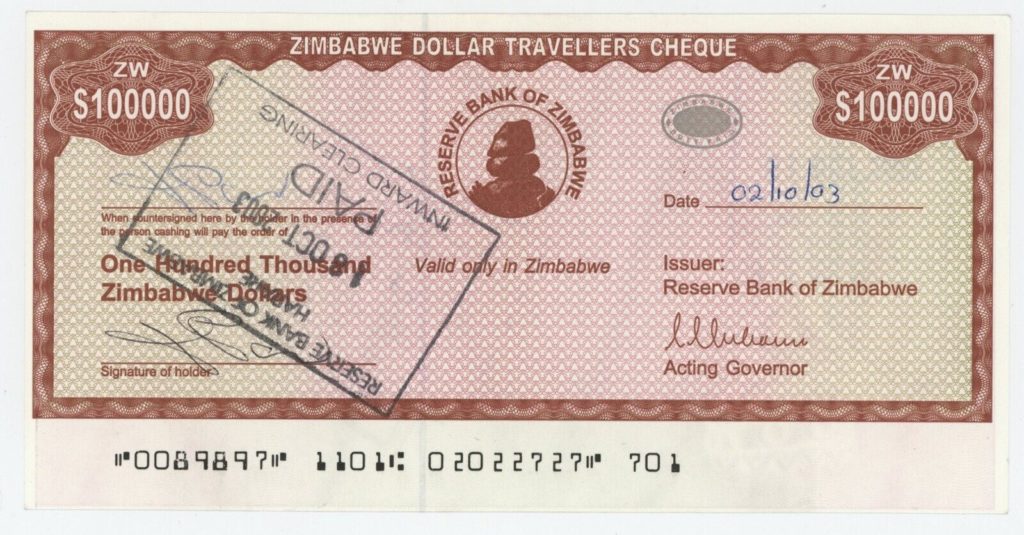

Spiraling inflation and the subsequent demand for high values of cash compelled the monetary authorities to introduce ever increasing values of cash denominations. At one point in 2003, the Reserve Bank printed local currency travelers’ cheques denominated between ZWD1000.00 and ZWD100 thousand. The cheques were only redeemable domestically but were useful for high value cash payments. However, these short-lived instruments were withdrawn from the monetary system after just four months in circulation. It is not quite clear why they were withdrawn so quickly but commentators say there were some opaque legal issues that caused their premature termination. The high nominal values of the travelers’ cheques were early indicators of the dire cash situation. Long queues at bank branches and ATMs became normal as clients waited hours to withdraw scarce cash. Much of the cash was now being directed to a thriving black market for foreign exchange, which was also now in severe short supply. A solution was needed, even if it was going to be a temporary one. That stop gap measure came in the form of a sweeping currency revaluation.

The First Restatement

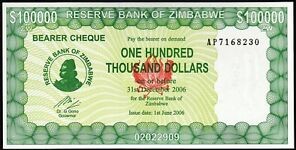

The initial revaluation of the Zimbabwe Dollar was carried out from 1 August 2006 to 21 August 2006. This first redenomination revalued the currency by a factor of 1,000. Banks applied the same revaluation rate to bank account balances. Depositors were given a three-week period that August month, to return their old bank notes to their bankers where they were able to make deposits and also to withdraw the new money now limited by daily withdrawal limits set by the Central Bank. By this time, the nominal value of the largest bank note had risen from ZWD20 to ZWD1,000, but this range of notes existed alongside a series of Central Bank issued bearer cheques valued from ZWD5,000 to ZWD100,000.

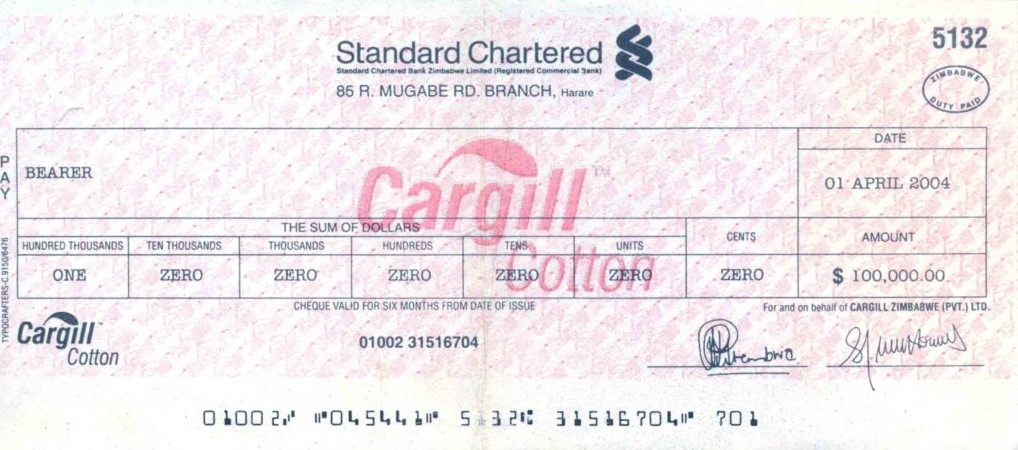

The bearer cheques had been introduced to manage a cash crisis that had ravaged the country and were issued with an expiry date of 31 December 2006. The idea of bearer cheques may have been spawned by cotton merchants who needed large volumes of cash to use during the cotton buying season. Tobacco and cotton had traditionally been bought from smallholder farmers in cash because for many of the largely rural farmers, maintaining bank accounts was inconvenient, impractical in remote rural areas, and also costly. With small value notes in circulation, the cash volumes were too cumbersome to handle, and they with the consent of the Central Bank, had begun issuing exchangeable cheques made out to bearers and drawn on their accounts at Standard Chartered Bank. This first lot of commercial bearer cheques were issued in 2003 and continued up to 2004.

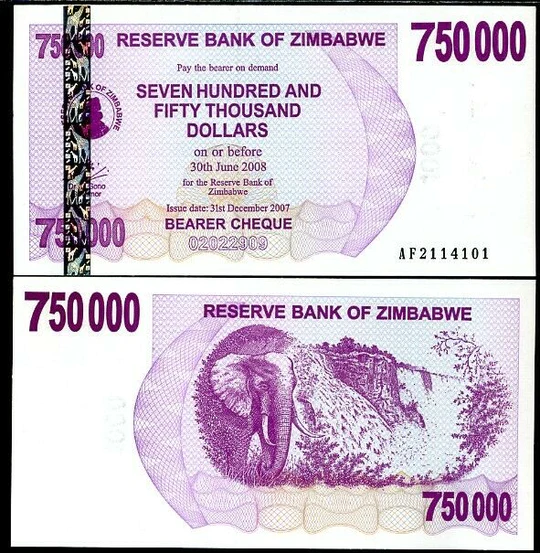

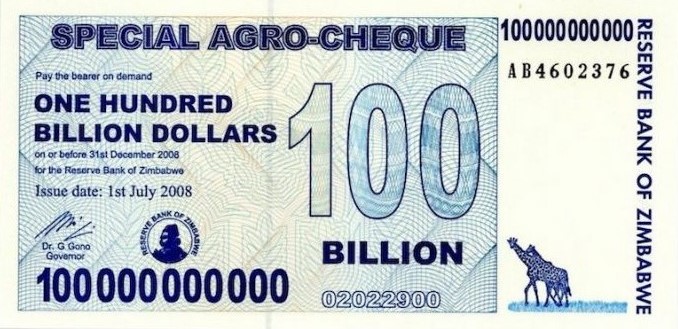

Currency revaluation in 2006 helped reduce cash volumes and also aided the transacting public in reducing the difficulties associated with dealing in large figures. However, it was not a long-term solution because the underlying problem of high inflation remained. The redenominated bearer cheque series of 2006 were valid from 1 August of that year to 31 July 2007 with an assigned currency code of ZWN. They were valued from ZWN1 cent to ZWN100,000. By February 2007, hyperinflation added to the enormous challenges the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ) was already grappling with, forcing the authority to introduce more bearer cheque denominations up to ZWN750,000. And yet this was not enough, mounting problems and raging inflation, now measured in billions, forced the release of even bigger denominations until the highest bearer cheque had a face value of a whopping ZWN500 million. A new class of bearer cheques also entered circulation. Special Agro-Cheques with face values of ZWN5 billion to ZWN100 billion were injected into circulation, at first to facilitate payments to farmers, but unavoidably ended up circulating publicly alongside other currency cheques.

Galloping inflation relentlessly caused prices of staple foods to soar, and the worst affected were the rural poor. The conditions in these areas worsened when government banned aid agencies from distributing food in the country, accusing them of using the food to campaign for the opposition. The Central Bank, which had for a long time, involved itself in quasi fiscal activities, initiated a program which it termed, BACOSSI, or Basic Commodities Supply Side Intervention, aimed at providing food hampers at token prices to low-income communal families. Under the facility, players in the food manufacturing industry whose capacity utilisation had dwindled following price controls instituted by government in June 2007, could access low-cost borrowings to increase production. The RBZ reported that after this intervention, capacity utilisation improved from low averages of 30%, to mid-tier averages of 50%, and in some cases, up to 65%. As a result, the supply of more affordable basics marginally improved in retail outlets. Food hampers containing maize meal, cooking oil and flour, among other items were subsequently made available to communal areas, providing relief from retailers who were accused of profiteering. However, many villagers claimed that the hampers did not reach all the intended beneficiaries, alleging that in some areas, ZANU PF supporters and war veterans, hijacked the hampers and blocked them from reaching perceived opposition supporters.

Another currency restatement

As prices looked skywards and the local unit tumbled, it became inevitable that a further currency revaluation was necessary, and on 1 August 2008, another 10 zeros were lopped off the currency. A new set of bank notes entered circulation along with another currency code, ZWR. The difference this time was that these were not bearer cheques, but rather formal bank notes that had been planned for an aborted release the previous year. However, with inflation running wild, the relief was again very temporary and a ZWR10 billion note was circulating by December of the same year. In January of 2009, bank notes were now valued in the trillions and Zimbabwe’s highest ever note with a face value of ZWR100 trillion was introduced into circulation. By this time, government had long stopped publishing inflation data, primarily because it was no longer useful, and also because it was extremely difficult to measure with any accuracy. For example, it became impossible for workers to budget for the commute to and from work, because the fare you paid to get to work would often more than double by the time you were going back home at the end of your shift. This became a real difficulty faced almost daily by public transport users. As a result, public transport operators and fresh produce market owners led the abandonment of local currency cash, openly preferring to transact in foreign currencies.

The USD and South African Rand (ZAR) were by far the most popular currencies for everyday transactions. In response, the RBZ announced new measures that licensed selected businesses to conduct their businesses in foreign currencies. Foreign Exchange Licensed Warehouses and Retail Shops (Foliwars), Foreign Exchange Licensed Oil Companies (Felocs) and Foreign Exchange Licensed Outlets for Petrol and Diesel (Felopads) were precursors to the adoption of a multicurrency system which the country officially turned to after other interventions failed. These specially licensed outlets pricing in foreign currency helped alleviate ongoing shortages because they allowed consumer goods that had disappeared from the shelves to return, albeit at elevated prices. Nevertheless, the principal problems with the local unit continued unabated.

Yet another currency restatement

The last of the currency redenominations occurred in February of 2009 when 12 zeroes were dropped effectively revaluing the currency by an unbelievable 1 trillion, and bringing with it yet another currency code, ZWL. A new set of bank notes was again issued and would commingle with the immediate prior series, but only for a little while, before being ditched in favour of a multiple currency regime. Because the Zimbabwe dollar had repeatedly lost so much value so swiftly, it was not uncommon, at least in its final days, to find Zimbabwe dollar cash strewn around on the streets or abandoned in bins. Eventually, the government was forced to legalise domestic trade in foreign currencies and this was done through a budget announcement made by the then Finance Minister, Patrick Chinamasa. That announcement spelt what looked like the final death of the Zimbabwe dollar. And when Tendai Biti took over as Finance Minister in a negotiated Government of National Unity, he put the final nail in the coffin of Zimbabwe’s fourth dollar when he demonetised it and refused to accept tax payments in the local unit. But as surprising as it may seem, and given the traumatic experiences of hyperinflation, no one could have foreseen at the time that the Zimbabwean Dollar would find a way to resurrect again. Before that, the country had to first find a political settlement, enjoy some stability, and then sneak its currency back into circulation.

Continue along with me, and find out later, how this resurrection was very gradually and cleverly achieved.

Follow and share The Book of Zimbabwe to learn about all the key events that shaped the Zimbabwe that the world knows today.

One Comment