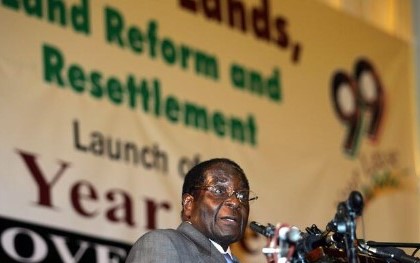

The intriguing Book of Zimbabwe – Part 8, Understanding the land problem

A brief history of Zimbabwe’s land problem

It isn’t possible to fully understand the question of land in Zimbabwe before dispassionately putting the entire story into context. In order to set the said context, it is necessary to journey back at least one hundred years into history. As far as many in the world know, issues with land ownership in Zimbabwe started when President Mugabe began a controversial program of compulsory land acquisition and redistribution in 2000. As international media reports go, the President sanctioned the occupation of white owned land in order to garner votes for upcoming Presidential elections where he faced stiff contestation from a young and increasingly popular opposition. The aspect of a strong and popular opposition is true but the other facts of the matter are distorted and do not truthfully represent all the issues. In an economic report circulated in October 2009, a widely respected economist, Professor Tony Hawkins, refers to a cabinet paper where some 6,214 farms covering 10.8 million hectares of commercially owned farmland had been taken over by the government since 2000. In his assessment this land was in fact expropriated from commercial farmers without compensation. You will notice how the term commercial farmers is used in place of white farmers to mask the fact that the real concern was that white people were losing land.

Of distorted narratives & unhelpful practices

This narrative of land confiscation is often repeated in many reports around the world and chooses to ignore the historical fact that this “commercial” land was originally annexed from its black indigenous owners over a hundred years earlier. Subsequent to that, the land has been sold and resold among white farmers up to the point where Mugabe’s government elected to reacquire the same, in principle, for the benefit of the masses. The Western point of view seems to hint that since the forcible takeovers were carried out over a century ago, then the descendants of the original owners have no claim to it. It suggests that the Zimbabwe government has obligation to compensate white farmers for land that their forefathers stole from the indigenous people. This, or course, is an unfair point of view but is just another typical example of the West’s double standards when it comes to Africa. It is helpful, at this time, in making the point, to recall that during World War II, the Jews unjustly lost countless lives in concentration camps such as Auschwitz and many valuable pieces of art were seized during criminal Nazi raids on Jewish homes in Germany and beyond. What is different in this case is that unlike Zimbabwe, the Jews eventually got compensation for these atrocities and in many cases, stolen art continues to be recovered even today and rightfully returned to Jewish owners, heirs and museums. Similar inferences can be drawn from the experiences of formally colonised black and brown territories around the world. But also, one has to understand that Western governments would be reasonably disinclined to support land reform in Zimbabwe, or anywhere else for that matter, because of the huge precedence it would set for the rest of the world, not least given Europe’s and indeed, the United States’ own colonial past and what it would mean if just one country were to succeed in claiming it’s land back from former colonialists. That said, what is unfortunate in the case of Zimbabwe, is that the land redistribution has been unhelpfully tainted by allegations of mismanagement, violence, chaos, corruption and nepotism which are difficult for anyone to deny. This makes the ethical case for land redistribution to disenfranchised locals less noble because numerous cases of self-enrichment and nepotistic land allocations overshadow the moral responsibility to right the historical wrongs.

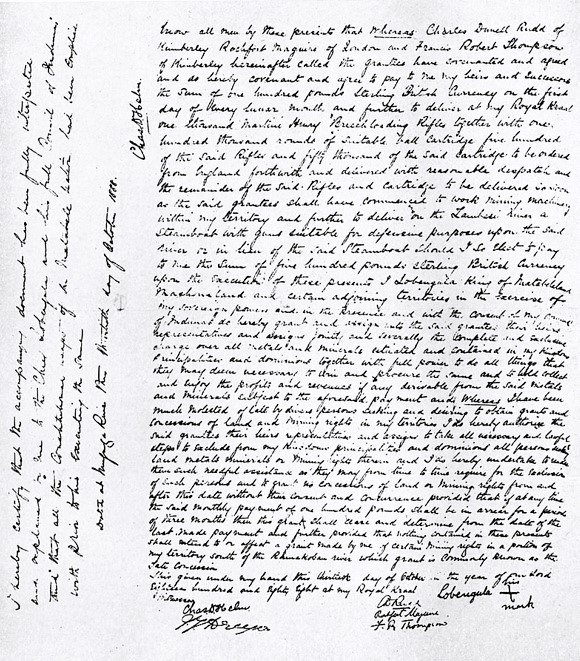

How to steal a country

Signed with an X by King Lobengula

As said earlier, we must take a brief journey into the past to understand how the land issue that plagues our nation today was born. Through trickery, manipulation and misrepresentation, a close business associate of Cecil John Rhodes, Charles Rudd, was able to secure the signature of King Lobengula of the Ndebele Kingdom for mining and administration rights in the Mashonaland region through what is now referred to as the Rudd Concession. This was possible because the Ndebele Kingdom had subjugated the Shona through brutal raids, murders and abductions of the various Shona groupings. Getting consent from King Lobengula was sufficient for Rhodes and his company to enter the Mashonaland territory without Ndebele resistance. However, mining was not the endgame for Rhodes who quickly sought to permanently colonise the territory before Lobengula inevitably became aware of the occupation plan. With the Concession now at hand, Rhodes used it to obtain a Charter from the British government which allowed him to act, although in limited ways, with the British government’s consent.

In the late 1800s, Rhodes dispatched a pioneering column of white settlers who made their way north east across the Tuli River eventually reaching what is now Harare. There, they setup a settlement defended from a hill known today as the Harare Kopje. Along the way, similar invasions and occupations had occurred in Fort Victoria, now Masvingo and Providential Pass as well as Fort Charter. Sponsored by investors of Cecil Rhodes’ British South Africa Company, their initial plan was to exploit minerals in the area but this fell apart when gold yields failed to meet projections and were overrun by the military costs of the incursion. To compensate the settlers from this Pioneer Column, and to appease investors, the mining plan morphed into an agricultural one. Land concessions were parceled out to European immigrants in the hope that they would establish farms that were productive enough to justify the continued cost of occupying the colony.

Initial resistance to occupation

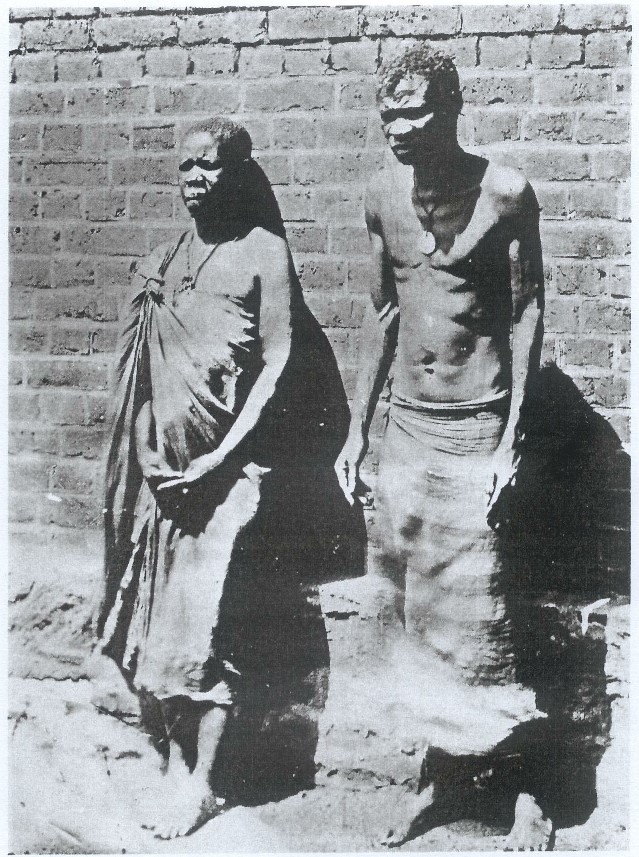

be spirit mediums who spoke for

Nehanda & Kaguvi respectively

At first, land was only offered to individuals who could demonstrate that they had the financial capacity to develop allocated farms but later, was offered to anyone willing to take up arms to fight-off the indigenous Shona and Ndebele people who were now beginning to resist the occupation. Inspired by historically towering figures like the spirit mediums of Nehanda and Kaguvi, and in some ways led by resistance figures like Mapondera, the locals put up a spirited fight against the invaders in the battles of the First Chimurenga War fought between 1896 and 1897. However, inferior weaponry and the fragmented nature of the resistance movements ultimately led to the poorly coordinated uprisings being brutally put down. Having managed to contain the uprisings from the Ndebele and Shona people, the settlers disbanded their pioneering column and established themselves as farmers competing for resources with the local people. As both the settler population and livestock numbers – also looted from locals – grew, pressure on the natural resources rose and their access to superior weaponry allowed them to forcibly push the indigenous people off their land.

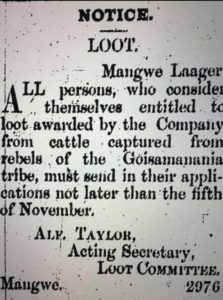

prepare to share the spoils from a raid on locals

in Matabeleland

The white minority colonisers eventually set themselves up as the governing authority in the territory now named Southern Rhodesia in honour of Cecil Rhodes who had envisaged the idea of the Pioneer Column and its capture of the territory. A series of laws, taxes and Acts introduced over time by the minority state effectively legalised the expropriation of fertile land and livestock from the blacks who were then forced into tribal trust lands that had poor soils and low rainfall and resultant low yeilds. The black people’s way of life began gradually being eroded as they were catapulted into Western ideologies, religion and social organisation. Many of the indigenous men had to start looking for employment to earn money to pay the various taxes that were introduced by the settler regime and this was of course deeply resented by the locals. The stage was now set for a decades long political and military conflict between the races of this Southern African country. That military conflict eventually came sometime in the 1970s and forced a political settlement that fell short of conclusively addressing the grievances of the blacks, particularly on the contentious issue of land ownership. As a result, that political disputation has not seen a true end, even decades after independence. As much as the players have changed, the interests at play have not, but we must necessarily briefly shelve this conversation to first introduce another problem that Zimbabwe has which is relevant and critical to a clearer understanding of the country’s challenges – the problem of high-level corruption.

Please share and subscribe to stay up to date with the Book of Zimbabwe as we progress to the next chapter of the fascinating story of Zimbabwe.

2 Comments