The intriguing Book of Zimbabwe – Part 10, How sanctions came & how sanctions work

And now the storm

Now that the historical context is set, it is now possible to explore how these seemingly disparate elements came together to spark the Zimbabwe sanctions regimes and the headline grabbing crisis that have come to define more than two decades of the Zimbabwe narrative.

First it was the unfullfiled promises

Sometime during the 1990s, disgruntlement by indigenous people in the communal areas started nearing a tipping point. More than ten years after independence, little progress had been made towards fulfilling the promises of the liberation struggle. People lost loved ones whilst others had sacrificed their livelihoods towards the goal of liberation and regaining their lost land. During the armed conflict, people were promised office jobs, decent homes and plentiful to eat. However, it seemed none of these promises were coming to fruition. Save for the 3 million hectares distributed before 1987, the land largely remained in the hands of the whites. Neither the jobs nor the decent homes were materialising. ESAP which was supposed to stimulate economic growth, job creation and tame inflation, was actually causing the job market to contract and the cost of living to spiral as subsidies were removed. On the other hand, however, the ruling elite had slowly become a class unto themselves, whilst it seemed, the people, and the war veterans especially, were forgotten.

Then came the land invasions

Out of frustration, sporadic invasions of white owned commercial farms started to happen. These invasions were localised and not sanctioned by the state. Most such occupations were non-violent and were led by war veterans after mobilising support from surrounding communal areas. In many cases, realising how the farm invasions would look to the international community, the government would dispatch emissaries to try and persuade the invaders to leave the farms. In some instances, where persuasion failed, the state had to use the police to evict the unauthorised occupants. The news spread and more and more reports of similar events began popping up around the country. Pressure was mounting from the grassroots for the government to take decisive action. The 1997 war veterans’ bonuses bought the government some time, but did not resolve the underlying problem of land hunger. Many of the people in the rural areas surrounding the commercial farms remembered how these white farmers had ill-treated them before independence, and remembered also, where their traditional lands were before their forefathers were dispossessed of their land.

And then the British reneged on their commitment

Development – Clare Short

But it was when Anthony Charles Lynton Blair, better known as Tony Blair, and his Labour Party assumed power in the United Kingdom in 1997, that conditions for Zimbabwe were about to get worse. Blair’s government infuriated Mugabe when they refused to acknowledge Britain’s historical responsibilities in Zimbabwe. In a letter to the then Minister of Agriculture and Land, Hon. Kumbirai Kangai, Clare Short, who was Secretary of State for International Development, said that Prime Minister Blair’s government did “not accept that Britain has a special responsibility to meet the costs of land purchase in Zimbabwe.” This letter destroyed Zimbabwe’s relationship with Britain and brought to an end, any hope that the former colonial power would honour the promises made by Lord Carrington at Lancaster. With escalating tensions in Zimbabwe over land redistribution, few options remained for President Mugabe and his administration.

Plus a costly foreign war and an electoral loss

The 1998 DRC war added to the mounting problems that the government had to deal with. Unbudgeted military spending in that war and the subsequent domestic borrowing coupled with excessive money printing to close budget gaps spurred inflation. International financiers and donors reduced their support to Zimbabwe. The ZCTU organised protests added a further dimension to the difficulties because it showed just how unpopular ZANU PF had become. When the MDC was formed in 1999 and after leading a successful “Vote No” campaign in the 2000 constitutional referendum, ZANU PF sensed the mounting threat to its continued rule and as a last-ditch effort to save itself, it tacitly gave its nod for farm takeovers to go ahead.

Fast-track land reform

The fast-track land reform program was born out of a confluence of unresolved historical issues and threats to the political power of the ruling party that were emerging at the time. Weeks after the loss at the referendum in February 2000, rural groups of Mugabe supporters organised by the Zimbabwe National Liberation War Veterans Association (ZNLWVA), began marching onto commercial farms forcing white farmers and their workers off the farms before occupying them. It is reported that seven white farmers and tens of black farm workers lost their lives during the skirmishes at various locations where a total of more than 100,000 square kilometers of land was taken over.

Perhaps for political expedience or due to an overwhelming number of people involved in the farm invasions or maybe for both reasons, government appeared to have taken the position to look the other way as the farm occupations took place. They moved quickly to create a reactive framework to legalise the land repossessions announcing a Fast Track Land Redistribution Program (FTLRP) in July 2000. The FTLRP authorised the government to take over identified commercial land without compensation for allocation to indigenous people. Under the new law, the acquired land became state property and could be leased out to beneficiaries whom the state would have deemed eligible and suitable for the two classes of farms, A1 and A2. The A1 model allocated small plots for growing crops and grazing land to disadvantaged landless farmers, while the A2 model allocated land to newly identified black farmers who had the skills and resources to farm profitably at a commercial scale. It is important to note that the ruling party always had an excess of the Parliamentary majority that was needed to push through constitutional amendments or to make new laws. The referendum may have been an attempt to secure a public seal of approval for the constitutional changes that the party had wanted to introduce. Now that, that route had failed, they were now legally using their Parliamentary advantage to have their way.

Commercial farmers had frustrated earlier paced land reform efforts

For a better understanding of how we got to this point, it is essential to highlight that earlier in 1992, the government had passed the Land Acquisition Act which empowered the government to acquire any land that it deemed fit for takeover but with a requirement to pay negotiable compensation. This program was to be staggered over five years, acquiring an average of 10,000 square kilometers of farmland per year. This was a partial departure from the Lancaster House Constitution which required farm acquisitions to be on a willing buyer and willing seller basis. Despite what appeared to be initial cooperation from donors and also from the Commercial Farmers Union, which had offered 15,000 square kilometers of land for the first phase, its members moved with lethargy when it came to the actual implementation, often making unreasonable price demands for the farms. Obviously, this frustrated the government along with the people who were meant to benefit from the program. From that perspective, the white farmers had not helped themselves by antagonising their stakeholders as they did. Events that followed the failure of the Land Acquisition Act, then could not be contained when the escalation to farm invasions occurred.

How the world responded

As one might expect, both the domestic and global response to the FTLRP was varied, reflecting the individual interests of the parties that responded. On the one hand, Western regimes were strongly opposed to the FTLRP because of the precedent it would set for other countries, particularly countries of the global south that faced similar issues of historical land ownership imbalances. It was therefore critical for the west, to send a strong and unequivocal signal to all who were following land related developments in Zimbabwe. The message was that, white property rights were off limits. On the other hand, most African governments and other nations from the global south, either openly or quietly supported the program or chose to remain publicly neutral whilst tacitly supporting the move in order to avoid a falling out with the powerful Western political and economic bloc.

Decision of the SADC Tribunal

One other exception to the almost unified response from Africa was the SADC Tribunal Ruling of 2007. When approached by a white farmer of South African descent whose farm had been compulsorily acquired, the Tribunal ruled in favour of the farmer arguing that several of his rights had been violated. Ruling on four main points, the five Member tribunal found that, it had jurisdiction to hear the case, that the plaintiff had been denied fair access to domestic courts in Zimbabwe, that the plaintiff had been racially discriminated against, and that the plaintiff had a right to be compensated for the land taken from him. This was in spite of amendments that had been made to the constitution which had given the government authority to acquire land for redistribution and also in spite of the decisions of domestic courts that had interpreted the constitutional amendment number 17 as giving effect to the government’s authority. Through a series of internal machinations, the Tribunal was for all intents and purposes eventually suspended when the terms of the incumbents expired and were neither extended nor new appointments made. It is speculated that the decision to let the Tribunal remain suspended was brought about by its verdict on Zimbabwe which the SADC Heads of States did not approve of. Interestingly, a related challenge made in a South African court sided with the SADC Tribunal’s ruling and ordered compensation for three farmers from Zimbabwe whose farms had been acquired under the FTLRP. In what is thought to be legal precedent history, the South African court ordered the seizure of Zimbabwe government assets in that country to compensate the plaintiffs. Appeals made by Zimbabwe to both the High and Supreme Courts of South Africa in the case were dismissed.

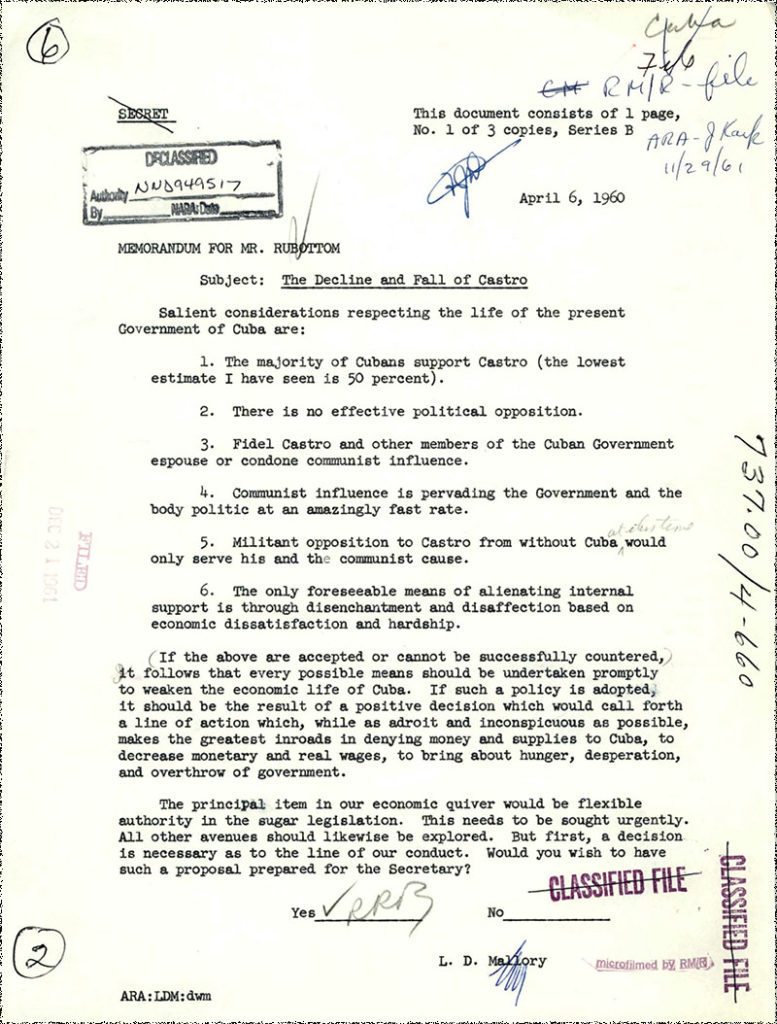

How the West predictably responded – lessons from Cuba

To understand how the west might have responded to this redistribution policy, one can look at the United States’ response to a similar action undertaken by Fidel Castro when he wrestled power from US backed Fulgencio Batista. Batista was a despised dictator who allowed US corporations and business people to own and control a large proportion of land and businesses in a racially segregated Cuban economy. When Fidel Castro and his guerrilla supporters overthrew Batista in 1959, he implemented land reforms which gave ownership of land to the workers who had previously toiled the land for little pay. The United States was not pleased and looked for ways to overthrow Castro but were not able to find a strong enough opposition political party within Cuba, whom they could partner and support for this purpose. They then opted for a strategy to topple Castro by causing economic hardship to trigger an uprising in Cuba.

of unilateral US sanctions on Cuba

In a declassified memorandum to the White House on Cuba regarding “the Castro problem”, the Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs, Lester Mallory, proposed that “the only foreseeable means of alienating internal support [for Fidel Castro] is through disenchantment and disaffection based on economic dissatisfaction and hardship. The memorandum went on to say, “if the above [strategies] are accepted or cannot be successfully countered, it follows that every possible means should be undertaken promptly to weaken the economic life of Cuba. If such a policy is adopted, it should be the result of a positive decision which would call forth a line of action which, while as adroit and inconspicuous as possible, makes the greatest inroads in denying money and supplies to Cuba, to decrease monetary and real wages, to bring about hunger, desperation and overthrow of government.”

Source: Office of the Historian

Not long after the memorandum was written, the United States took steps to strangle the supply of petroleum to Cuba. These actions and a series of other developments eventually forced Fidel Castro to nationalise oil refineries in Cuba, most of which were American owned, ultimately leading to sanctions which have remained in place for more than 60 years now. This despite an almost unanimous call by the United Nations General Assembly over the last 30 years to have them removed. Since the first set of conditions which prompted the US to impose its unilateral sanctions on Cuba, other political factors have resulted in various other US sanctions being imposed on the country, but our focus for this discussion remains on the land redistribution related economic restrictions. If Cuba can be used as a yardstick of what to expect for Zimbabwe, then it would be obvious to infer how the US and its allies would deal with the Zimbabwe problem.

Indeed, Western response to the fast-track land redistribution program in Zimbabwe broadly followed the outline of the Cuba plan. ZANU PF has long accused the opposition MDC party and its subsequent iterations up to the present CCC, of being complicit in the imposition and sustenance of sanctions and of being foreign funded – more specifically, Western funded – and if true, this would gel well with the United States’ first instance plan to deal with Castro in Cuba through domestic opposition. Widespread reports of land seizures, acts of election violence, rights abuses, intimidation, perceived undemocratic electoral laws and skewed access to public print and broadcast media have marred elections in Zimbabwe since the entry of the MDC into Zimbabwean politics. ZANU PF has alleged that the opposition triggers or stages incidents of violence and other political misrepresentations to tarnish the country’s image in order to court Western sympathy. These reports were used by Western countries, led to action by the British government, as the leading factors in the collective decision to enact various incremental sanctions and other restrictive measures on Zimbabwe beginning in 2001. When examined in totality, the argument for sanctions on this basis falls short in that many other countries with similar electoral shortcomings do not have sanctions imposed on them. For Cuba and Zimbabwe, the key differentiator is that these countries undertook land reforms which dispossessed white people of land without compensation.

How United States Sanctions systematically destroy economies – the Zimbabwe case

As previously indicated at the beginning of the telling of the story of Zimbabwe, there is no consensus among Zimbabweans about the impact of sanctions on the country. Officially, the sanctions on Zimbabwe are targeted only at a small evolving list of individuals and entities accused of directly or indirectly aiding or of being complicit in rights abuses and undermining democratic processes in the country. Proponents of sanctions argue, with a fair measure of reasonable cause, that the reasons offered for enacting the sanctions are sound, and that since they are targeted, they have no impact on the wider economy or persons not listed. For example, unlike the sanctioned individuals, ordinary Zimbabweans face no travel or international payment restrictions that sanctioned individuals have. “How are sanctions affecting you?” is the question often posed on social media when some Zimbabweans opposed to sanctions have voiced their opinions, and at this point, many such voices are silenced. Instead, sanctions backers say that corruption, cronyism and economic mismanagement are the sole reasons for the hardships facing the nation. One cannot in all honesty dismiss the corruption and mismanagement argument because it has substance, but its failure point is in refusing to accept that sanctions, in their current form, are deliberately designed to draw economic development backwards. In many ways, ordinary Zimbabweans would indeed fail to see any impact of sanctions on them, but this is also due to the reduction of the argument to the person rather than the machinery of the economic system. Every cog has a part to play in the smooth running of an economy, and if the larger cogs cannot move, then the entire machine can grind to a standstill, and this is explained in more detail by people who were themselves involved in crafting sanctions on other countries.

Parallels with Iran?

Richard Nephew was appointed by the US Joseph Biden administration to the position of Coordinator on Global Anti-Corruption sometime in July 2022. Before that, he was at one point, a Principal Deputy Coordinator for Sanctions in the State Department when Barack Obama was president. This qualifies him as a credible source of intelligence on US sanctions policy. In his book, The Art of Sanctions, Richard Nephew boastfully shed a lot of light on how US sanctions are designed to work. It is therefore both useful and important to understand them from his expert perspective.

It is common knowledge that Iran and the United States have had an acrimonious relationship for decades since the Iranian Revolution in 1979. Already agathokakological relations between the two countries completely soured when the Iranian Revolution deposed US backed Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlav. The revolution ushered-in a more inward-looking Islamic State headed by the Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, a Shiite cleric who opposed the Shah’s Westernisation of Iran. The Shah had himself been brought to power through a US and UK assisted coup which had removed Iran’s then Prime Minister, Mohammed Mossadeq. This came after Mossadeq had nationalised the British-owned Anglo-Persian Oil Company, which led London to impose an oil embargo on Iran. Since then, the United States has variously tried to bring about the overthrow of the government of oil-rich Iran using its policy of wide Iranian sanctions as one such tool. Richard Nephew used his experience in the State Department to pen a book in which he describes how the US and to some extent, its allies, use sanctions as a means to achieve their foreign policy ends. Reference is made to Iran sanctions which, much like the 1960 Mallory memorandum on Cuba, persist a policy to cause disaffection within the country through inflicting social pain on the civilian population.

An excerpt from Nephew’s book outlines the broad framework for sanctioning states to follow. In it, he correctly substitutes the word “pain” for “sanctions”, stating the sanctions framework as quoted in the following points;

- “Identify objectives for the imposition of pain and define minimum necessary remedial steps that the target state must take for pain to be removed;

- Understand as much as possible the nature of the target, including its vulnerabilities, interests, commitment to whatever it did to prompt sanctions, and readiness to absorb pain;

- Develop a strategy to carefully, methodically, and efficiently increase pain on those areas that are vulnerabilities while avoiding those that are not;

- Monitor the execution of the strategy and continuously recalibrate its initial assumptions of target state resolve, the efficacy of the pain applied in shattering that resolve, and how best to improve the strategy;

- Present the target state with a clear statement of the conditions necessary for the removal of pain and an offer to pursue any negotiations necessary to conclude an arrangement that removes the pain while satisfying the sanctioning state’s requirements; and

- Accept the possibility that, notwithstanding a carefully crafted strategy, the sanctioning state may fail because of inherent inefficiencies in the strategy, a misunderstanding of the target, or an exogenous boost in the target’s resolve and capacity to resist. Either way, a state must be prepared either to acknowledge its failure and change its course”

Source: Richard Nephew’s book The Art of Sanctions (available for purchase here)

More specifically to Iran, Nephew goes on to explain how the US made the situation even worse for Iranians by ensuring that economic reforms in Iran planned by President Ahmadinejad’s administration would fail. One of the objectives was to ensure that the country is drained of its foreign currency reserves thereby further weakening its economy. Again, I quote;

“The United States took steps to ensure that these reforms would remain difficult to achieve, starting with the sanctions themselves as well as NOT imposing sanctions on things like humanitarian, consumer, or luxury goods that might have helped Iran reduce its import bills. With Iran’s population technically able to purchase such goods and imports still flowing in, but with the exchange rate depriving most people of the practical benefit of being able to purchase these goods, only the wealthy or those in positions of power could take advantage of Iran’s continued connectedness. Hard currency streamed out of the country while luxuries streamed in, and stories began to emerge from Iran of intensified income inequality and inflation.” “This was a choice, a decision made on the basis of helping to drive up the pressure on the Iranian government from internal sources. The currency crisis in October 2012 helped crystalize this point, with Iranian protesters taking to the streets out of frustration over their meager take-home earnings. The United States and its partners used their knowledge of the Iranian revolution story and fear of economic discord as a deliberate way of prying apart the regime and the population, making the previously easy sell of the dignity of Iran’s nuclear program far more costly.”

Source: Richard Nephew’s book The Art of Sanctions (available for purchase here)

imposed targeted sanctions on Zimbabwean interests

As this relates to Zimbabwe, the country does not have a nuclear program, instead, it has a fast-track land redistribution program that drew the ire of the UK, the US and the collective West. Economic discord, hunger, desperation and inequality arising from US sanctions have also made the government’s redistribution policy more difficult to sell. If anything, some black people have actually started looking back to colonial times with nostalgia, saying the days of oppressive minority rule were better. In this regard, one of the sanctions’ objectives, “to separate the people of Zimbabwe from ZANU PF”, is certainly beginning to work. This is not to say the Zimbabwean government holds no responsibility for the turbulence in the economy and in the political environment, it does, notably through its failure to reign-in corruption and mismanagement of public financial affairs. The point being made here is that US sanctions have a leading part to play in the country’s troubles.

Yet more parallels with Iran

There remain yet more parallels with Iran. For instance, the poor state of public health services provision is one aspect that can be blamed on the government as well as on the impact of sanctions. The government’s response to sanctions and poor actions to circumvent or resolve them has led to a continued decline in services at public health institutions. With a few exceptions, Zimbabwe’s public health facilities, medicinal drug stocks as well as staff compensation have fallen into a deplorable state. News reports are awash with stories of collective job actions, power and water outages, equipment failures, bed and food shortages as well as drug and medical consumable stockouts. Maternity care has declined considerably whilst specialist care for chronic conditions like cancer or kidney failures requiring dialysis are virtually non-existent. Ambulances are in short supply or require patients to pay fees that are not affordable to the poor. Cases have been reported of patients using undignified modes of transport like carts or wheel burrows to get to medical centres. Needless to say, many lives have been unnecessarily lost due to these many shortcomings. So bad are the circumstances that it is not uncommon for locals to travel to other countries in the region or further for medical attention. This has strained relations with neighbours such as South Africa, which has become a preferred destination for Zimbabweans seeking free public health services. Recently, some provinces in South Africa have started asking foreigners to pay for services that are given to South Africans for free. To be fair to our neighbours, the requirement for foreigners to pay is not unreasonable given that governments budget resources for their own populations and so, taking on additional burden from other countries can lead to inefficiencies or even collapse of their own health systems. In short, conditions are not good for low-income Zimbabweans and government can be blamed, but not without apportioning a fair amount of blame on the wider effect of the US sanctions which will be explained shortly.

Returning to the example of Iran, under US sanctions, the country faced similar problems with health delivery. Sanctions are an act of economic war and as it relates to medical care, that economic war affects the poor the most. Richard Nephew suggests in his book, that whilst the impact on medical services may not have been intended, the US government is aware of the unintended consequences but presses ahead with the sanctions anyway. The following is another quote from his book, The Art of Sanctions;

“Even sanctions regimes with humanitarian carve-outs can contribute to humanitarian problems because of the broader effects of the measures selected. In Iran, for instance, there were reports throughout 2012 and 2013 that medicine and medical devices were unavailable not because their trade was prohibited but rather because they cost too much for the average Iranian due to shortages and the depreciation of the Iranian currency. The United States and its partners, through sanctions, directly contributed to the depreciation of the Iranian rial and, consequently, played some part -even if unintentional- in the creation of this problem.”

Source: Richard Nephew’s book The Art of Sanctions (available for purchase here)

As can be seen, the sanctions agenda is very methodical and well thought-out. Teams of experts craft these policies and others are responsible for their implementation and monitoring. The final parallel that can be shown to exist between Iran and Zimbabwe is one that might not have been so obvious but for the exposé offered by Nephew’s book. It is one of mobile phone penetration. Many regimes under pressure from Western interference, tend to control mass media and the broadcast of information. Certainly, the state-controlled broadcasters and print media in Zimbabwe stand accused of churning out propaganda on behalf of ZANU PF. In fact, the achievement of fair access to public broadcast and print media by the opposition is one of the conditions stated as riders for the lifting of US sanctions on Zimbabwe. To go around this problem, in Iran, the United States took additional steps to ensure that mobile phones were more affordable and easily accessible to Iranians, including the poor. This way, citizens were more able to share experiences of just how dire their economic conditions had become, driving anger and discontent among the population. Further, other sanctions restrictions were designed to create job losses, increasing unemployment thereby stoking disenchantment with the government. Here are Richard Nephew’s own words from his book explaining this point;

“The United States took its surgical sanctions approach a step further in June 2013 with a carefully structured set of sanctions on Iran’s automotive sector, denying Iran the ability to import manufacturing assistance but not spare parts for existing autos or whole cars themselves. Iranian manufacturing jobs and export revenue were the targets of this sanction, undermining the Iranian government’s attempt to find non-oil export sectors and ways of employing 500,000 Iranians. All the while, the United States expanded the ability of U.S. and foreign companies to sell Iranians technology used for personal communications, helping ensure that the Iranian public had the ability to learn more about the dire straits of their country’s economy and to communicate with one another..”

Source: Richard Nephew’s book The Art of Sanctions (available for purchase here)

The systematic targeting of key industries as well as the near universal penetration of low-cost communication devices is as true for Zimbabwe as it was for Iran. Mobile phone penetration rates in Zimbabwe of above 90% are among the highest on the African continent. Smart phone penetration on the other hand was reported at 52% in 2021 but is still considered high for a country experiencing a severe economic downturn like Zimbabwe. Could the general affordability of mobile phones also be the result of maneuvers by foreign interests? One can only speculate. Critically, because smart phones allow for internet connection, their accessibility to the electorate becomes a point of interest for political actors. It has been suggested by political commentators, although without evidence, that this could be one reason local authorities have introduced new taxes on mobile phone and data purchases. For its part, the Media Institute of Southern Africa (MISA) has backed parliamentarians who have urged the government to scrap the taxes to ensure that universal access to technology and the internet becomes a reality.

Even after sanctions de-listing – risk remains

President Mnangagwa )R)

Just as with Iran, US sanctions have hurt the local economy. At one point, Zimbabwe’s Industrial Development Corporation or IDC, was designated as a sanctioned entity, and with its shareholding tentacles spread across multiple industrial sectors, all entities in which it had a significant stake were also deemed sanctioned. This created insurmountable operational challenges for the IDC and its affiliated companies leading to the near collapse of many of them. Even after sanctions were lifted, financial institutions remain wary of transactions associated with formerly sanctioned entities which retain very high risk ratings. Just this specter of US sanctions and related penalties create a sufficiently untenable level of risk to deter foreign direct investment. The US authorities are aware of this and quietly allow it to cripple the local economy in pursuit of their foreign policy objectives. In an interview with CGTN Africa, US Democratic Senator Chris Coons admitted to the contagion effect of the sanctions and how they make almost the entire sanctioned jurisdiction toxic and risky for foreign investors in particular. In his own words, he attests that “relieving sanctions would provide significant economic lift for Zimbabwe” because it would “encourage foreign direct investment.” He also acknowledges that with its highly educated population, a legacy of infrastructure and abundant resources, Zimbabwe would otherwise be an attractive investment destination but for the detractive effect of sanctions on the economy for “as long as there are significant sanctions in place by Western countries on Zimbabwe.”

Some reforms are needed – unilateral sanctions are not helping

It is therefore not misguided to view sanctions as acts of war, because they in fact are. What makes the sanctions on Zimbabwe especially wrong, is that they are unilateral. The relevant United Nations body, the Security Council, that has the power to authorise the imposition of sanctions, refused to do so when a draft resolution was brought before it in 2008, however, Western powers continued with their illegal sanctions regimes anyway. Whilst it is not in dispute that the Zimbabwean authorities should urgently look at the case for electoral and economic reforms in the country, even the national constitution adopted in 2013 requires them, the rules for imposing sanctions should

still be followed. Acting otherwise, is often to the detriment of powerless citizens who bear the brunt of receding economies, but then again, that is the whole point of the sanctions. A widely followed and respected global award winning journalist has previously agreed that sanctions do not help and so too has a sitting opposition MP. This is not to say that necessary reforms should not be carried out, but with sanctions, the power structures will continue to dig-in, and we will have more disputed elections. Nobody wins.

In the next instalment, we discuss more of the politics and the calamitous economic downturn that followed the imposition of sanctions. Please share, comment and subscribe to stay up to date with The Book of Zimbabwe.

2 Comments